I shared the team’s mistakes with everyone, then this happened…

A few years ago, I led a product development effort at an enterprise. We were constantly experimenting, so had our fair share of wins and failures. But I had the feeling that we weren’t learning from mistakes quickly enough.

Large organisations maintain risk registers, which usually keep details of risks and issues. We also had a risk register, but it was being treated as one of those documents created for the sake of documentation.

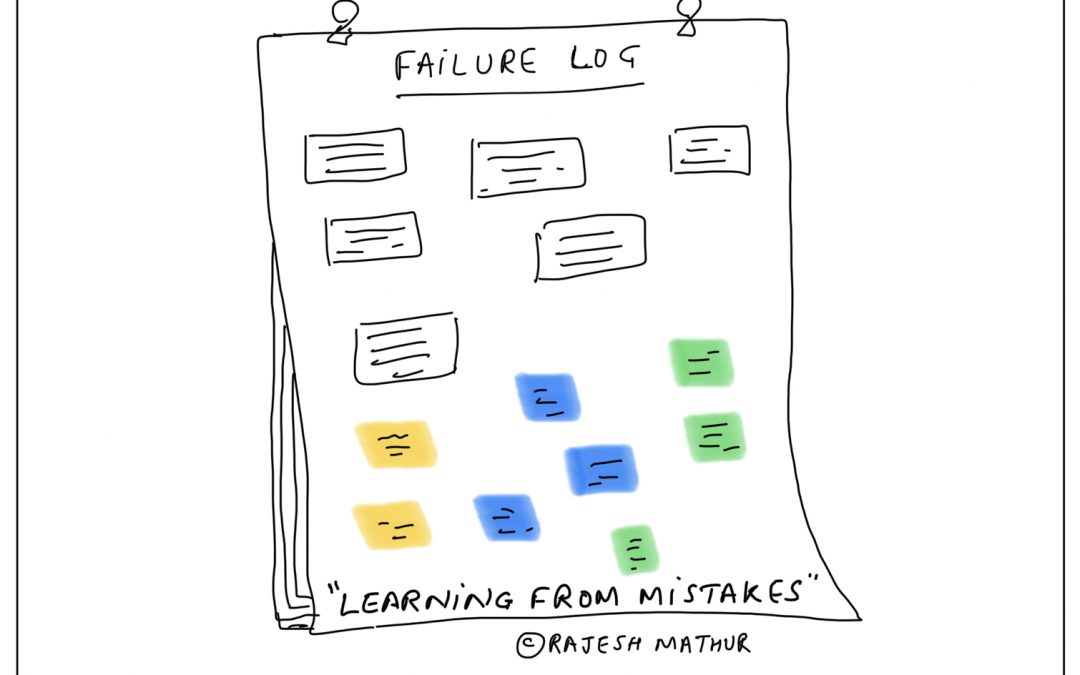

Frustrated, I decided to put a poster on the wall with the title “Failure log”.

Why the heck a failure log?

The team reacted differently to the failure log. Some were amused, some confused, and some annoyed.

The annoyed ones saw this as exposing their weaknesses.

The confused ones didn’t know how showcasing our mistakes was going to help the project.

Others were happy that we were taking an initiative that could not only build psychological safety, but could also help us learn from our mistakes.

My challenge was that the organisation was not very mature. It was very much a command and control environment, so having the courage to publicly admit you’d made a mistake was a bold move, and to some extent a risk.

It was a risk because the board and the management team had invested heavily in the program and they were watching our progress very carefully. It was quite possible to face unintended consequences of making mistakes. In other words, it could have been a career-limiting – or perhaps even career-killing – move.

Luckily, the Chief Product Officer I worked with was progressively minded. He encouraged and supported experiments. Plus, the Program Director and I had become friends and she supported everything I did. Both could understand my vision and wanted to be part of it.

We were like a start-up within a traditionally managed enterprise.

Many of the team members, including the Product Leads and the Innovation Manager, were itching to do more and my bold step encouraged almost everyone to step up and forward.

I started adding smaller mistakes and things on that poster that could have been improved.

The Blunder!

And then one day… it happened!

A team member mistakenly sent a test email to hundreds of customers. It was a PR and Communications disaster.

You may be wondering why a test web page was connected with a production database?

The web page was built for a fake door experiment and the idea was to expose a very small number of customers to that page.

We got through that issue… but the question around recording that mistake on the Failure Log felt almost as tough.

The team was divided on sharing an embarrassing mistake with everyone else. Specifically in an environment where we were expected to have Gantt charts, detailed project plans, roadmaps, scripted test cases, and God knows what else.

So, what did we do about sharing the mistake?

After a bit of discussion within the team, we decided to include the mistake on the Failure Log because that was the right thing to do. There was a consensus about being congruent.

What happened after taking that major step?

I was sacked… right?

No. Nothing major happened at all. We were warned to be more diligent in future. That’s it. I thank my lucky stars for that.

Lessons that I learned:

But something did happen that was major for me:

- The team became bolder

- The experiments we quietly discussed earlier turned into open discussions

- More items appeared on the Failure log, which by now had become the learning log

- More and more visitors from other departments wanted to learn from us

- And the best of all, the cohesion and collaboration among team members (as well as with the management team) improved

Taking a bold step, and then taking another courageous step on top of that, taught us many lessons and made us a great team. We delivered value to customers, and we were more open about our outcomes. Best of all, the tea cohesion improved.

I can’t ignore the fact that the senior folks I worked with made it easier for me to take bolder steps. If executives aren’t supportive, then forget about experimenting with new ideas.

The failure log was an experiment that could have gone in any direction. It could have become a political mess, or quietly died from lack of interest.