Perception and Perspective

“Hey Rajesh, there is a perception that you don’t do <X>!”

The consultant that the company had hired told me.

“Oh! Who in the team think that I don’t do <X>?

“Mate, I can’t tell you that. But perception is reality.”

Only after few years of leaving that place I found out that it was him who created a perception. He wanted more influence (and more business) and I used to question things. Well!

In that case, I did not receive any useful and actionable feedback. This is unfortunate that such scenarios are far too common where people receive vague comments instead of actionable feedback.

At Microsoft, we use the word “Perspective” to get our colleague’s point of view about how one is performing, what they are doing well and where they can improve. This mechanism allows people to receive all-round feedback and not just someone’s perception.

So, what’s the difference between perception and perspective?

Can you define each of those clearly? Most people find it hard to explain what they mean by perception and perspective.

Yet, both of these things are important for us to understand the world around us, assign meaning to what we observe and then decide whether to act or not.

You may hear some people saying that perception is reality, but I find that unintelligent. Saying that is only an excuse for not thinking clearly and critically.

What is perception and perspective?

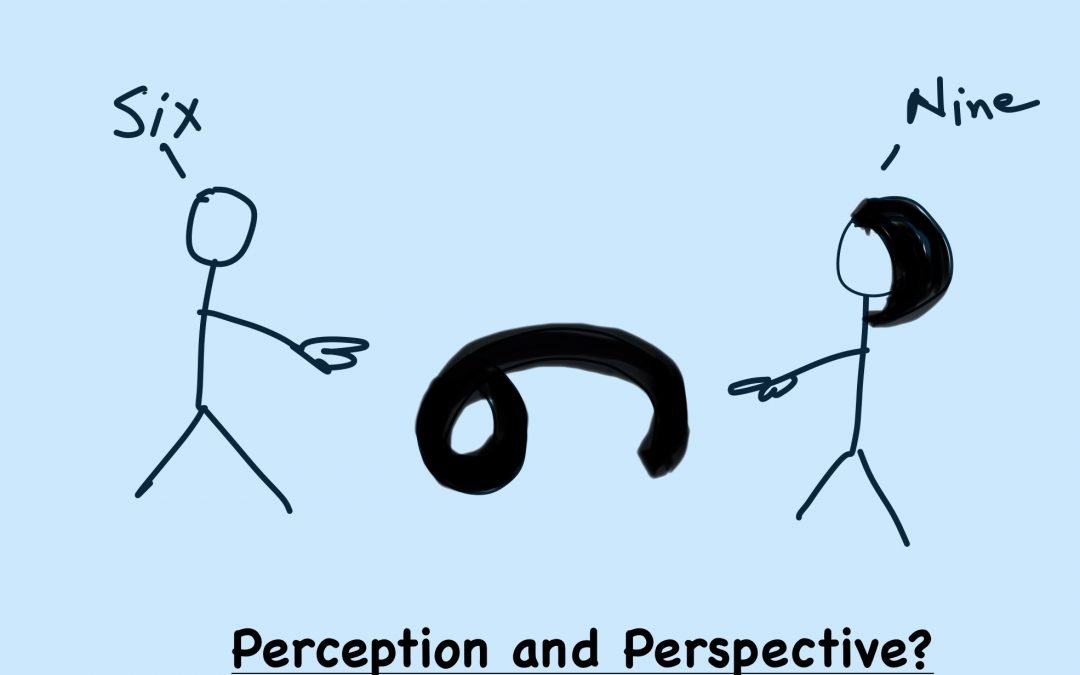

Perception is the interpretation of things that we see, hear, smell or feel. It is what we ‘believe’ we understand after receiving a sensory input and then define a meaning that we apply to a situation, person or a thing.

For example, look at the cartoon above. Depending on how you look at it, you can easily perceive number six (6) to be number nine (9). You may even fight with someone about being right.

Perspective comes via and after perception. In other words, perception leads to perspective. It is our point of view that we build based on our perception.

If you are thinking that both perception and perspective will together in determining how we interpret things and build a point of view, then you are right.

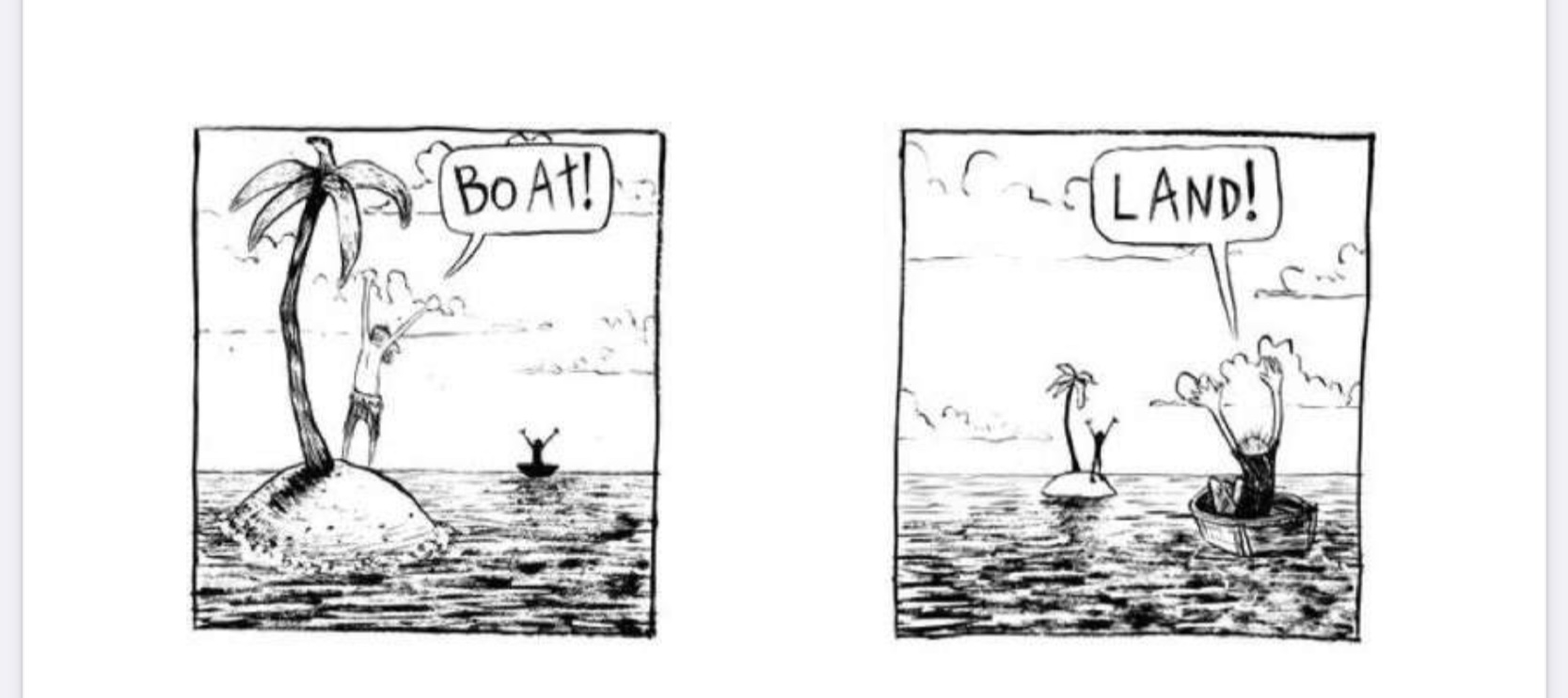

This cartoon that I found on internet is also a good example of how perception of a given situation creates a point of view (perspective).

The image below is a good and powerful example of how perception and perspective play an important role in building our PoV.

- What will you perceive if you only look at the first part of the image?

- What will you think if you only see the last part of the image?

- What is your point of view about the situation?

- After seeing the full image, did your perspective change?

Note: The above image was created by Ursula Dahmen. Find the details here: https://www.spiegel.de/fotostrecke/manipulierte-bilder-fotostrecke-107186.html

What was surprising for my own interpretation of the above image was to discover that the soldier on the left wasn’t pointing the gun at the other soldier’s head. It was strapped to the soldier’s back.

Even that interpretation might not be correct until we hear the truth from the horse’s mouth.

Perception and perspective in work scenarios:

Passionately debating is quite common in some cultures.

It is also natural to have debates and discussions at work. A person who is only an observer and noticing the arguments, all the back and forth from both sides and sometimes the treated voices out of passion might perceive the debate as a fight.

This observer might build a point of view that the people debating are causing trouble at the workplace and might decide to complain about them to their seniors.

Based on this observer’s complaint, the senior folks might build a perception too and decide to take punitive action against the people who were merely debating a topic related to their work.

So, while perception is not reality, it may manipulate the reality. Unless one seriously pays attention, find all facts about a situation and critically examine them, perception may turn into a belief.

As managers, leaders, parents or friends, it is our responsibility that we learn about our perceptions and do not let them affect our perspective merely through quick judgement.

That is not easy, but at least we can try.