Agile team practices that showed us immediate results

There are times when culture and the practices that a team follows (or does not follow) start affecting their delivery work, primarily in Agile teams. Non-essential meetings, unplanned or unwanted catch-ups, feeling lack of safety that forces people to keep record of things such as emails, are often part of a bigger problem.

As a delivery professional (Lead, manager, Scrum Master and in some cases even product owners), your responsibility is to ensure that your teams delivers the valuable outcomes, at frequent intervals and with a sustainable pace. This responsibility also includes protecting them from non-productive tasks and mentoring them for de-prioritising non-value adding tasks.

Unfortunately, sometimes teams do not even realise that some of their practices were slowing them down. This often happens because of a rigid mindset that is ingrained in their organisations and the cultures. And as you might already know, it takes time to change behaviours and attitudes that become norms.

The good news is that you can possibly change that mindset.

How do you do that?

The answer lies in the teams. Teams are built of people, and people prefer to stick with social rules. In fact, it is often hard for people to oppose or show resistance to norms of a group that they are part of. As an Agile delivery leader, it is in your and the organisation’s interest that you encourage your teams to develop a social contract or a working agreement. These contracts define how the team members in a team prefer to work together and what they find as acceptable behaviours. Since everyone in a team contributes and agrees to the principles of a social contract, it is also easier to improve practices that affect them most.

Just to be clear, these social contracts are not legally binding agreements. They are there to enforce the values and principles that people in a team believe in and agree to adhere to.

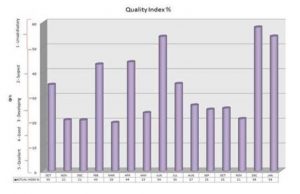

I was working with this team of nearly fifty people as a delivery manager. The team was consisting of four product streams and there were interdependencies. We were facing some common challenges regarding the day to day functioning of the team. Through the retrospectives, I came to know that there were few common patterns across those streams where the teams were feeling the pinch.

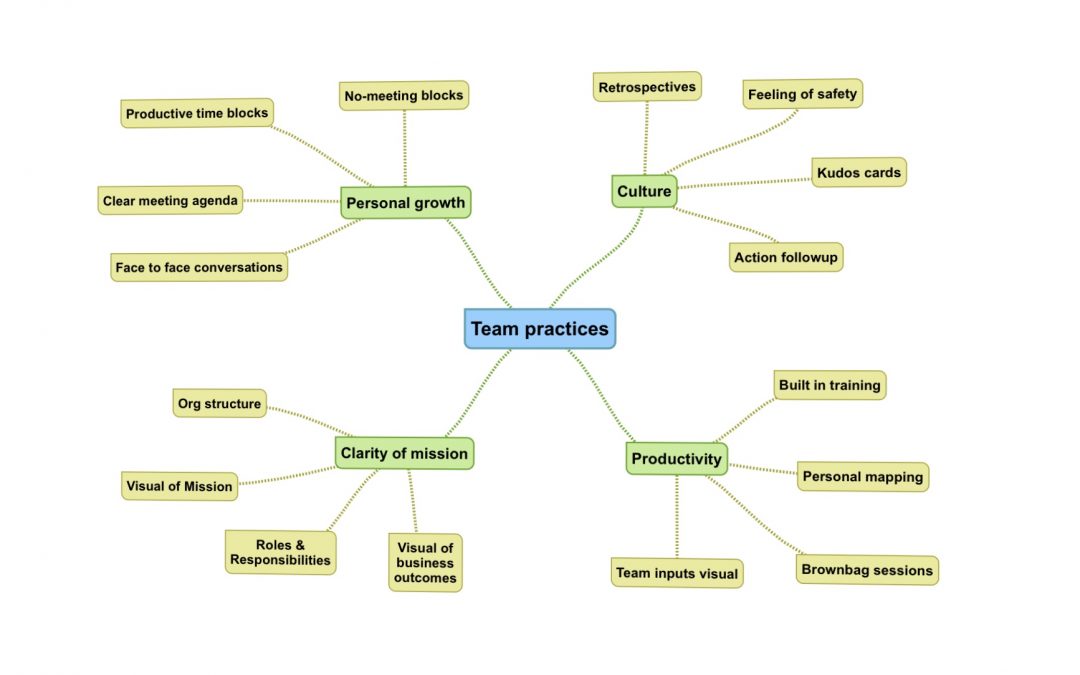

I was able to break those patterns in four themes:

Productivity (and process improvement)

Culture (behaviours & attitudes)

Development & growth

Clarity of Mission

All of these themes can be summarised in some of the key challenges:

– Too many meetings. Many of which unplanned and go on for too long

– Lack of agenda and expected outcomes in meeting requests

– Lack of a medium for team members to appreciate their colleagues across the program

– A need for a common platform for the whole team to come together and share ideas

– Finding time for training or capability uplift

– A need to know each other better which was a challenge due to the size of the group

– Clarity of roles at program level

Here’s how we solved the problems:

Productivity + process improvement:

There were too many meetings and this large number of meetings was not only affecting productivity, it was also impacting delivery schedule. Since meetings were reducing productivity, team members were also getting visibly annoyed.

This is what the team decided to do:

- No one within the team was allowed to schedule meetings after 3 PM. What that meant was that people get unrestricted productivity time after 3PM.

- Everyone in the team agreed that each meeting request will have a clear agenda and if possible, the outcome they were looking for.

- We also attempted to limit the meeting times. That is, any 30 minutes were planned for 25 minutes and any 1 hour ones were planned for 45 minutes.

- We also asked people to come prepared so that their messages were concise and crisp.

- We emphasised on face to face conversations whether people were onsite or working remotely.

We kept an eye on these practices for adherence and ensured that everyone, specifically the senior team members behave like role models.

Culture:

The program director and I were closely aligned on the values that everyone in the team adheres to. Having a shared understanding at the management layer certainly ensures how each member of the team will behave.

- We encourage team members to be completely open and honest in retrospectives and otherwise too. We also made sure that our own behaviour reflects what we were advocating for.

- I attended and at times facilitated team retrospectives. What was motivating for me was that often team members approached me after the retrospectives showing their appreciation for making them feel safe in those sessions. Team retrospectives were purely for the team members and neither product owners nor anyone from the program team were allowed to attend unless required.

- We made sure that the program management team accepts the improvement areas and takes actions. We circulate those actions to the team members so that they can see the congruency.

- We also ensured that we provided regular updates on the status of the action items.

- To encourage peer to peer appreciation, we introduced “Kudos cards” in the program. When we introduced the cards, we also explained why there was more value in appreciating those who deserve and why a reward system from management does not work.

- Monthly retrospectives: Due to the interdependence within the streams, it seemed vital that the whole team has a common retrospective. Team retros also reflected that need. Hence, we decided to schedule a monthly retros for the whole team. In these sessions everyone in the team came together to share ideas openly and respectfully.

Development & growth:

Many project or product teams do not have additional budgets for training for their team members. Depending on the structure of the organisations, team members might belong to different specialist groups that are responsible for their professional development. Sometimes People and Culture (a.k.a HR) teams are responsible for arranging training. Dealing with some of these processes can be cumbersome due to bureaucracy. So what do you do then? Well, see how might you get your team some training and mentoring. We found the answer in some unconventional ways. We agreed that you don’t always have to separate training from ‘business as usual’. Therefore:

- We build small pockets of training time in each team event. We had a quarterly team events calendar and we specified training time in the calendar. For example, to enhance team collaboration, we added a ‘personal mapping’ exercise in a monthly showcase. Easy!

- We placed a flipchart in the project room with suggestions as well as space for other ideas. Team members could either opt for an existing training sessions or could suggest a new one. There was enough autonomy to add anything and we did see some funny suggestions too.

- We made sure that there were options for lunch-time sessions, brown-bags, separate training and even ad-hoc sessions. Once we organised a session on user stories by extending our stand up to an extra 30 minutes. What you might find hilarious that we expected 5 attendees, but nearly 25 people showed up.

Clarity on roles:

Sometimes within large teams, where you are adding new members regularly, it is difficult for team members and leads to explain various roles (just to be clear, I’m not talking about titles here). In our case, we had data architects, data engineers, CX designers, UX designers, delopers, testers, business analysts, solution designers, legal counsels, procurement people, scrum masters, product managers, domain architects and others. With so many roles, not only explaining them can be hard, but also keeping them clear to avoid overlaps. You don’t want people unknowingly stepping on each others’ toes. Neither you want any frictions among team members, no matter how psychologically safe you believe your team is. We’re all humans after all!

- We created a team structure chart that clearly showed who was working on what. We also made sure that the chart shows which stream people belonged to. We circulated this chart to everyone in the team and also added it to our induction pack that we shared with all new team members.

- Although I am not a big fan of RACI matrix (responsible, accountable, consulted, and informed), it deemed necessary to us to create one. Of course we consulted our team about what they thought about it.

Why I’m not a big fan of RACI matrix? Because these matrix define linear responsibilities. That is, one person = one specific role. If you are a self organising team, you may have team members playing different roles. However, having this chart helped us bring more clarity about roles and it also reduced overlapping and multiple channels of similar conversations. Additionally, team was clear that their self-organisation wasn’t at risk. - Skill matrix: Now this is something that was interesting. I had used skill matrix before to create cohesive, well designed, self supported teams. What a skill matrix does is to show the availability, lack of and level of expertise for a particular skill. For example, you may have someone very experienced in C++ and you may also have someone willing to learn it. As a lead, you can take actions to balance the skill shortage. For me, this experiment failed as no one ever willingly added their skills. I also trouble validating why that happened. Anyways, this was added to our ‘Failure log’.

As you might have noticed, we solved many of our problems by bringing people together. Creating common understanding was our first step in ironing out some of the challenges we faced. We also did a number of experiments and not all of them were successful. However, keep running short experiments, validating them through feedback loops and not losing focus from your primary goal can do wonders for your team.

Did you do something similar in your organisation? How did that go? Let me know in comments.